The order of the five offerings in Leviticus 1:1-6:7 is theologically significant. After all, nothing in God’s Word is random or accidental. Accordingly, many theologians have noticed that the five offerings display the overall pattern of worship for God’s people, which I wholeheartedly agree with and will summarize below. Even so, I also suggest another dimension to the ordering of these offerings, namely, that they beautifully correspond to the five books of the Torah. But before we can explore those potential connections and their implications, let me give a brief summary of the five offerings.

THE FIVE OFFERINGS AT A GLANCE

The five offerings listed in Leviticus 1-6 are, as named in the ESV, the burnt offering, the grain offering, the peace offering, the sin offering, and the guilt offering.

The burnt offering comes first because it is the most basic of all the offerings. Indeed, it is made by the priests in the morning and the evening to open and close each day’s time for making sacrifices. The purpose of the burnt offering was atonement for sin, not for specific sins but for sinfulness in general. Whenever an Israelite brought a burnt offering, he or she was acknowledging that they are a sinner in need of forgiveness and restoration before Yahweh.

The grain offering is also called the tribute offering because it was given for the purpose of acknowledging Yahweh’s kingship. In the tabernacle system, this offering was exclusively grain, either raw or uncooked, which is why it is called the grain offering.

The peace or fellowship offering is third. Its name shelamim likely comes from the word shalom, which means peace, well-being, or wholeness. Leviticus 7 informs us that this offering was split three ways: a portion went to Yahweh, a portion to the priests, and a portion was eaten by the worshiper. It was a communion meal that testified to the restored peace and fellowship that the worshiper had with Yahweh.

The sin (or purification) offering differs from the burnt offering in that it was made for specific sins. Particularly, it was made for unintentional sins. Kenneth Matthews writes that “the sin offering was God’s provision for the guilty person by which his or her sin was purged and by which he or she received divine forgiveness” (44).

Finally, the guilt offering is also made for specific sins but emphasizes the worshiper making reparation for his or her sin. It is a picture of sin as a debt and how the worshiper can properly repent. It also carries the theme of restoration, to God as the offended party and of the worshiper back into peace with God. Or perhaps we can put it like this. If the purification offering taught that only God can cleanse us of our sins, the guilt offering emphasizes the need for obedience as evidence of true repentance.

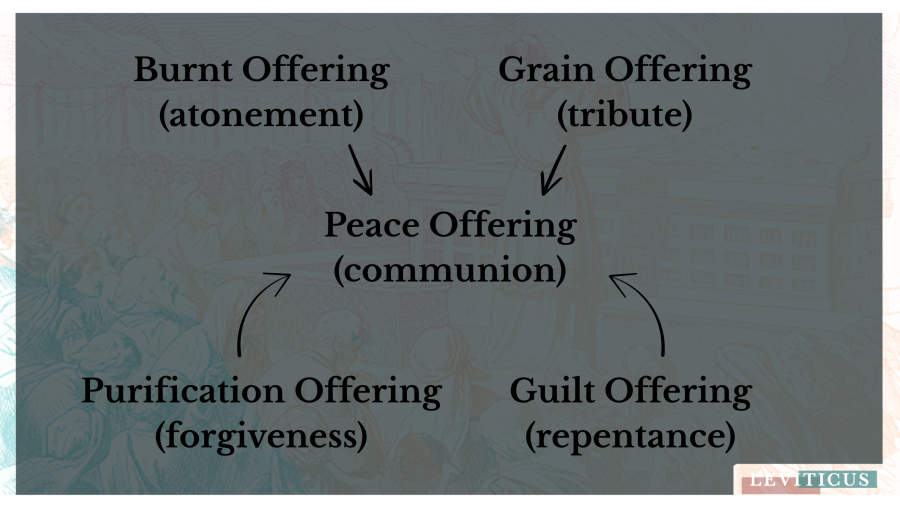

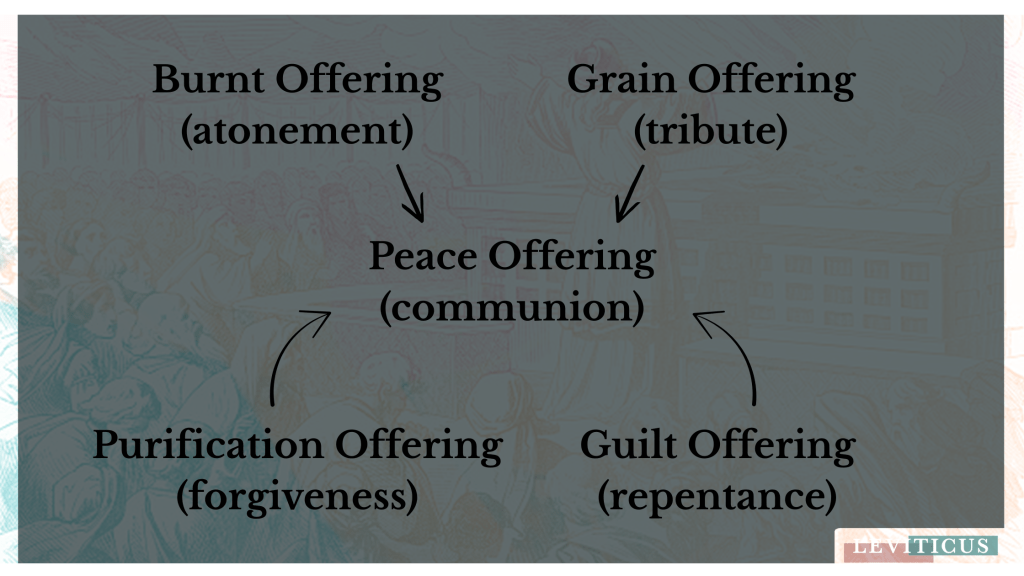

These five offerings form a pattern for worshiping Yahweh. Morales explains (note that he calls the burnt offering the ascension offering):

The first three offerings (ascension, tribute, and peace) taken together and in order present an ideal worship scenario… The second two offerings (purification and reparation) were expiatory in nature, required as a remedy for particular sins.

Indeed, the burnt and grain offerings are movements toward the peace offering, and the sin and guilt offerings are about restoring the worshiper back into fellowship and peace with God. Peace and fellowship with God cannot be established without atonement for sins and tribute to God as God. As Christians, we can think of this as confessing Christ as both Savior (atonement) and Lord (tribute). Yet our sin continues to disrupt our communion with God, which must be answered through repentance, especially confession, restitution, and renewed obedience.

FIVE OFFERINGS / FIVE BOOKS

With the overview of the offerings and their purpose in mind, consider with me how they might correspond to the five books of Moses, also called the Torah or Pentateuch. This idea came to me while studying for Leviticus 3 and the peace offering. It struck me that the peace or fellowship offering might be strategically listed as the central offering because it conveys the central idea behind the offerings as a whole: drawing near to God for communion with Him. Of course, I am also convinced that communion with God is the overall theme of Leviticus as the central book of the Pentateuch. Thus, I argued in my sermon that the peace offering presents us with the theme of Leviticus in a nutshell.

But what about the other four offerings?

There seem to be plenty of thematic parallels between Genesis and the burnt offering. They are both foundational. The burnt offering is the most basic and fundamental of all the offerings, while Genesis presents the beginning of every major biblical theme and doctrine. Also, just as the burnt offering requires acknowledging one’s overall sinfulness, Genesis tells us how sinfulness in general came into the cosmos. But the burnt offering is not simply about recognizing sin, it is offered to make atonement for sin. Repairing humanity’s exile from God through sin is one of the chief questions underlying Genesis’s narrative. After giving us humanity’s downward spiral in 1-11, chapters 12-50 focus on Abraham and his family as bearers of the hope for humanity’s redeemer.

The grain offering, again, is intended as a tribute to God as the King of kings. Consider then Exodus. Chapters 1-14 focus on Yahweh liberating Israel from the wicked kingship of Pharaoh so that they can serve Him as their king. When they come to Sinai, God tells them that they will be His kingdom of priests. The second half of the book focuses on Yahweh’s covenant with them and how He will dwell with them through the tabernacle. We could even say that the golden calf was a kind of anti-tribute offering, for the people of Israel attributed their salvation from Egypt to the idol that they made.

Numbers could be said to correspond with the sin or purification offering through the sin of Israel that is repeatedly on display throughout the book. Indeed, Matthew Henry notes that Numbers can be summarized by Psalm 95:10: “For forty years I was grieved with this generation.” Yet even as God purifies Israel through judgment (culminating in the purging of the entire exodus generation), God is still merciful to His people. In spite of their continual sin, God still forgives them and embraces them as His people.

Finally, Deuteronomy is about Moses’ final sermons to Israel before they finally enter Canaan. In this book, Moses reminds them thoroughly of their sin and of God’s law, renews the covenant with the new generation of Israelites, and summons them to loving obedience to God’s commandments. Indeed, just as the guilt offering emphasizes the depth of sin as a breach of faith (a transgression against God’s holiness), so Deuteronomy gives us the heart of God’s covenant and commandments as well as how God’s law is to be renewed among God’s people. The guilt offering is a picture of true repentance (which turns from sin and toward obedience), which brings the repentant sinner back into communion with God, and that is largely the message of Deuteronomy as well.

Does not the shape of the Pentateuch correspond to the pattern of the five offerings? Genesis establishes the world’s corruption under sin and presents our need for redemption. Indeed, the whole burnt offering is often seen as representing the consecration of the worshiper entirely for Yahweh, which is imaged beautifully (though imperfectly) by the life of Abraham, the father of God’s people. Exodus then establishes Israel as being under Yahweh’s kingship, and Leviticus details how exactly they can have peace and fellowship with the LORD as He dwells in their midst. Numbers and Deuteronomy both show how their peace and fellowship can be disrupted by sin but also how God is determined to restore communion with His people.

WHY THIS MATTERS

If the five offerings in Leviticus do indeed correspond to the five books of the Torah, then their pattern emphasizes the centrality and supreme importance of God’s Word.

Indeed, Leviticus itself is a testament to this truth. Even though it describes the tabernacle system of worship, which was never designed to be permanent, the book is saturated God’s direct speech. The phrase “And Yahweh spoke to Moses” or some slight variation is used 37 times. Andrew Bonar notes that no book in Scripture records more of God’s direct words than Leviticus. Thus, if we get too lost in the particulars and details, we might lose the main point that Leviticus is God’s Word about how His people can draw near to Him.

The thematic connection between the five offerings and book of the Torah highlights that, while the physical acts of the offerings were temporal and designed to pass away, the Word of God is eternal. As Jesus said, “Heaven and earth will pass away, but my words will not pass away” (Mark 13:31). The tabernacle system was temporary, but the Scriptures are not. The very presentation of the offerings declares that truth.