And the LORD spoke to Moses, saying… As we prepare to hear these words from God, let us warm our hearts beside the spiritual flame of Psalm 19. We have seen in verse 7 that God’s law is perfect, reviving the soul, and sure, making wise the simple. Now in the first half of verse 8 we read: “The precepts of the LORD are right, rejoicing the heart.” Thus, we move from God’s word enlivening and wizening to delighting.

Of course, this may not be exactly what we expect. Few things are as offensive as saying that God’s precepts are right because, since so much of the Scriptures contradict us, that necessarily means that we are quite often wrong. Indeed, we would have no problem calling what the Bible says right as long as it always agreed with us. After all, we know best how to make ourselves happy, right? Well, despite our culture’s insistence on following your heart and being true to yourself, anxiety and depression continue to skyrocket. Maybe, just maybe, the God who made us knows better than us how to make us happy. You see, as much as the lie of the serpent still whispers to the contrary, acknowledging the Scriptures are right and living in obedience to them rejoices the heart. Through obedience we learn that God’s commandments really are for our good (Deuteronomy 10:13). May that be our prayer as we study God’s word this morning.

THE ORDINATION CEREMONY

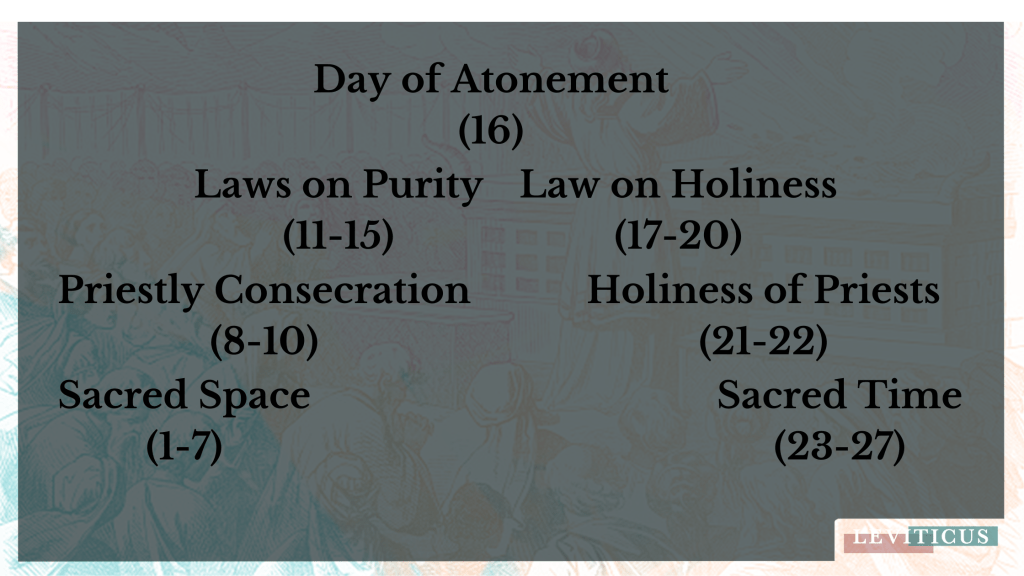

With Leviticus 8, we enter into the second major section of the book. As I said in our first sermon of this series, Leviticus can broadly be divided into two halves: 1-16, which focus on drawing near to Yahweh, and 17-27, which command how God’s people were to live holy lives to Him. Yet Leviticus can also divide into seven sections which form a chiasm with the Day of Atonement at the center. With chapter 8, we are now entering the second of those seven major sections.

Leviticus 8 describes the consecration of Aaron and his sons as the priesthood. We’ve already studied in Exodus 28-29 a description of the garments the priests were supposed to wear, as well as a command for this ceremony of consecration. Now, in our present text, we come to the ceremony itself.

I think Alan Ross is correct to identify a sevenfold structure to this ordination service (the priests were witnessed, washed, clothed, anointed, atoned, ordained, and installed), and that is the outline we will follow in our passage. We’ll walk through the seven parts of this ordination, or consecration, service (you’ll notice that I’ll use those two words interchangeably throughout).

Our structure for each part will be twofold. First, I’ll explain the text itself—what was happening in the different aspects of the ordination service for the Levitical priesthood here in our passage. Then, we’ll make application for us today. Because under the new covenant in Christ, the role of the Old Testament priesthood gives us a reflection of our own calling as Christians. As 1 Peter 2:9 says, we now belong to a royal priesthood. We are all priests in Christ Jesus, who himself is our great High Priest. So, we’ll walk through this passage and then reflect on how all seven of these elements point to Christ as our great High Priest.

Witnessed // Verses 1-5

First, in verses 1–5, the priests were witnessed by the congregation. I love what Alan Ross says:

Because these men had spiritual authority over the people, it was imperative that the congregation witness their consecration as priests in order to be convinced that they were made priests by God. The people of Israel needed to know that these priests were accepted by God. (209)

But I would also add that it was important for the priests themselves to see who was representing them before God. Priests stood as mediators between God and man. The people needed satisfaction both ways. They needed to affirm, “These men truly represent us,” but they also needed to see God’s satisfaction with those men. The priests had to be fitting to the Israelites, and they had to be fitting to God, because they stood in between as mediators.

Notice that the text says this was to happen at the entrance of the tent of meeting (vv. 3, 4). This was very likely in the courtyard of the tabernacle. Typically, when Scripture speaks of the whole congregation, it means the entire nation, but the courtyard was certainly not big enough to fit so many people at once. So, here the congregation likely refers to the elders of Israel, gathered to represent the whole nation.

We too have a responsibility to bear witness to one another and encourage one another in the faith. We are all witnesses of each other’s faith in Jesus Christ, and we are to affirm that faith to one another.

We see this formally in church membership. To join a church, you must be affirmed by the membership; and conversely to be excommunicated, it must also be by the membership as a whole. The elders can’t just decide on their own. Membership is guarded by the collective witness of the entire congregation. Being a member of a church is a formal testimony to your fellow members, affirming that you are a Christian and a follower of Jesus Christ, while excommunication is the whole body (your brothers and sisters in Christ at your particular congregation) saying to you, “Repent. We do not see evidence that you are living out your calling as a Christian.”

Informally, this witness also happens in all the “one another” commands throughout Scripture: love one another, bear with one another, encourage one another. We are constantly witnessing to one another. This shows us that, while it is technically possible to be a lone-wolf Christian, it is incredibly unwise. We need each other’s testimony. We see Christ most fully in his Word, but also in one another, since we are the body of Christ and have his Spirit. We need each other for this walk of faith. We are witnesses of one another as we journey together toward the celestial city, to borrow Bunyan’s metaphor.

Washed // Verse 6

Second, the priests were washed, which we see in verse 6. Before anything could begin, Aaron and his sons needed to make themselves ceremonially pure through washing with water. Kenneth Matthews notes that, “Aaron could not approach the Holy God unless he himself was spiritually prepared. This corresponds to the symbolism of an unblemished animal that the priest alone could offer up” (79).

We’ll talk more about ceremonial purity and impurity later in chapters 11-15, which address cleanness and uncleanness, purity and impurity. But here, we simply need to see that Aaron had to make himself ceremonially pure before anything else could be done.

Of course, we also mark our initiation into the body of Christ with a washing: baptism. And, like the washing of Aaron and his sons, baptism does not literally remove our sins. I do not believe that Aaron and his sons thought that washing themselves in the bronze basin was cleansing them of sin. It was a picture, a real-world symbol of what only God can do spiritually.

In the same way, baptism does not actually wash away our sins. It is a sign of the true spiritual washing that Christ performs on our hearts through his Holy Spirit. And, of course, baptism is a public confession that this cleansing has taken place. So, we too must be washed before we can perform the work of ministry Christ has called us to do (Ephesians 4:12).

Clothed // Verses 7-9

Third, the priests were clothed in their special garments. We looked at this when we studied Exodus 28 last year. The colors of the priestly garments, which are not mentioned here but are worth recalling, were the same colors as the tabernacle. I think this gives us the best clue to their overall significance. When the priest clothed himself, he was symbolically clothing himself with the tabernacle, binding himself to the tent of meeting. In a sense, the priest became part of the tabernacle system.

But this also had another use. Ordinary Israelites were never allowed inside the tent of meeting. They could only enter the courtyard, never the holy place or the most holy place. So, the only glimpse they ever had of the beauty within the tabernacle was the priests’ garments as they came out to minister in the courtyard. Remember, the outside of the Tabernacle was not impressive to look at; it was covered with leather hides to protect it from the elements. The priests’ garments were, therefore, the visible glimpse of the tabernacle’s beauty to the people.

Now all priests wore four main garments: undergarments (to preserve modesty while ministering), a tunic, a sash, and a headband. The high priest, however, had additional garments unique to his office. He wore a blue robe that likely symbolized royalty. He also wore the ephod, which had twelve gemstones, each representing one of the tribes of Israel. Every time he put it on, it was a reminder that he carried the twelve tribes on his heart as he ministered before the Lord. He also had a breastpiece, which contained the Urim and Thummim—terms that seem to mean “lights and perfections.” These were used for decision-making before the people. Finally, the high priest wore a special turban with a gold plate inscribed with the words holy to the LORD. This was a constant reminder that he was Yahweh’s instrument on earth.

In his letters, Paul often uses clothing imagery for the Christian life. He tells us to “put on the Lord Jesus Christ” (Romans 13:14), “put on the imperishable” (1 Corinthians 15:53), “put on Christ” (Galatians 3:27), “put on the new self” (Ephesians 4:24), and “put on the whole armor of God” (Ephesians 6:11).

Or we can look at Colossians 3:12-14:

Put on then, as God’s chosen ones, holy and beloved, compassionate hearts, kindness, humility, meekness, and patience, bearing with one another and, if one has a complaint against another, forgiving each other as the Lord has forgiven you. And above all these put on love, which binds everything together in perfect harmony.

So what kind of priestly garments are we to wear as the royal priesthood in Christ? Those virtues: compassion, kindness, humility, meekness, patience, forgiveness, and above all, love. This echoes Jesus’ words in John 13: “By this all people will know that you are my disciples, if you have love for one another.”

So what are we to put on as ministers of Christ’s reconciliation in the world (2 Corinthians)? Put on love. Put on compassion. Put on humility and patience. Put on the new self. Put on Christ.

Anointed // Verses 10-13

The priests were anointed with oil. The oil used for this anointing was a special blend of olive oil and spices that could only be used for holy matters (Exodus 30:23-30). We commented on that last year as well. There was nothing miraculous about the oil itself; it was no magic formula. Its significance came simply from God’s command. This oil was holy, set apart for use exclusively in the tabernacle and by the priests.

As for the spiritual significance, Kenneth Matthews explains:

The significance of the anointing oil was its symbolic association with the Spirit of God (1 Samuel 16:13; Isaiah 61:1). Priests, kings, and prophets received the Spirit, and in many cases they were simply known as “the anointed.” The oil represented the power of the Spirit that enabled the priests to carry out their duties. The Spirit’s presence distinguished the priests from the regular members of the congregation. (83)

So not only was the oil itself holy, but by pouring it over Aaron and his sons, they were being set apart for holy service.

Now, because all Christians are indwelt by the Holy Spirit, all Christians are also anointed by him. Paul affirms this in 2 Corinthians 1:21–22:

And it is God who establishes us with you in Christ, and has anointed us, [22] and who has also put his seal on us and given us his Spirit in our hearts as a guarantee.

This means that, contrary to what many argue, there is no special “anointing” for pastors, elders, or ministers today. All of us in Christ have been anointed by the Spirit. We have all been set apart. In fact, the very word saint means holy one, that is, set apart for God’s use. By calling us saints, Scripture declares that every believer has been anointed and consecrated to God’s purposes.

I love how Scott MacDonald puts it in an article on this topic. He says:

While the Bible contains no imperative to be anointed, Ephesians 5:18 commands us to be filled with the Spirit. Anointing is a trait of the entire church in the New Testament, but filling is not. Believers are commanded to pursue it, and it results in wisdom, knowledge of God’s will, heartfelt worship, and thankfulness. We would expect our leaders especially to exhibit Spirit-filling before the body, and the Spirit may occasionally use such people in powerful ways. But this does not mean we should misuse the biblical term “anointed” to describe them.

That’s helpful. It is better to speak of someone as Spirit-filled—walking in the Spirit, with the Spirit working powerfully in their life. And that is something all of us are called to pursue. But if you are in Christ, you have been anointed by the Holy Spirit.

Atoned // Verses 14-21

Fifth, the priests were atoned. Two offerings were made on behalf of Aaron in verses 14–21. First, a sin offering (vv. 14–17), and second, a burnt offering with a ram (vv. 18–21).

Now, ordinarily an Israelite would present both of these offerings as part of worship, but the order here is important. The purification offering came first because the priest himself had to be cleansed before he could present the burnt offering. The burnt offering then followed, offered on a purified altar by a purified priest.

Both offerings together pointed to atonement and forgiveness of sins. The purification offering dealt more specifically with individual sins, while the burnt offering addressed sin in a general sense. Together, they “covered all the bases,” so to speak. Why? Because priests were just as sinful as the rest of Israel. They were not naturally holier than anyone else.

For us today, just as the priests ministered on behalf of others with the knowledge that they themselves were sinners, so we too must minister out of humility. Whether we are supporting a brother or sister in Christ—helping them fight sin, walking with them through suffering—or sharing the gospel with unbelievers, we do so mindful of our own need for grace.

Jesus teaches this in Matthew 7:3–5:

Why do you see the speck that is in your brother’s eye, but do not notice the log that is in your own eye? Or how can you say to your brother, ‘Let me take the speck out of your eye,’ when there is the log in your own eye? You hypocrite, first take the log out of your own eye, and then you will see clearly to take the speck out of your brother’s eye.

Notice: Jesus does expect us to help our brother. If your brother has a speck in his eye, help him remove it—but only after you’ve dealt with your own log. The priests had to offer sacrifice for their own sins first before they could minister for others. Likewise, we cannot minister rightly until we see ourselves as sinners in need of a Savior.

So let me ask: when you serve, whether in discipleship or in evangelism, do you come as one beggar showing another beggar where to find bread? Do you minister as one who has been forgiven, pointing others to the same forgiveness that is found in Christ?

Ordained // Verses 22-30

Sixth, the priests were ordained or consecrated. This element is described with what’s called the “ordination offering,” also referred to as the “ram of ordination.” Scholars like Wenham and Sklar argue this offering was a type of peace offering, specifically for ordination. Without getting into all the details, notice two important aspects here.

Moses placed blood on the right earlobe, right thumb, and right big toe of the priest. As Allen Ross explains:

The application of blood to these parts covered what they heard, what they handled, where they went; it meant that in all their activities they were supposed to be set apart by the blood. Being a priest involved total sanctification of life—a holy lifestyle. This is confirmed by the sprinkling of oil and blood (8:30). There was no separation between sacred and secular; the priest was never off duty.

Yahweh’s food offering was placed in the priests’ hands before being handed back to Moses and burned as a pleasing aroma to the Lord.

The significance of this act comes across in the idiom for ordination, expressed in Hebrew as “to fill the hand.” Filling the hand means to install to priestly office (Ex. 29:9; Lev. 21:10; 1 Kings 13:33). The installation ceremony quite literally fills the hands of the priests with portions of the “ram of filling” Aaron and his sons begin their ministry by taking the gifts that have filled their hands and offering them back to the Lord in worship. (ESV Expository Commentary, Vol 1, 897)

For us today, the picture is clear. Just as the priests were set apart, so are all believers in Christ. Again, as 1 Peter 2:9 declares, “But you are a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a people for his own possession.”

Our hearing, our doing, and our going must all be consecrated to the Lord. John writes in 1 John 2:3–5,

And by this we know that we have come to know him, if we keep his commandments. Whoever says “I know him” but does not keep his commandments is a liar, and the truth is not in him, but whoever keeps his word, in him truly the love of God is perfected. By this we may know that we are in him: whoever says he abides in him ought to walk in the same way in which he walked.

To be consecrated today means obeying Christ. God has filled our hands with the good news of Jesus. He has marked us with the blood of Christ. We belong to him—and we must walk in obedience.

Installed // Verses 31-36

Finally, we see in verses 31–36 the installation of the priests. Gordon Wenham observes: “A man may defile himself in a moment, but sanctification and cleansing are generally a slower process” (83). This is reflected in the ordination ceremony. Defilement can happen instantly, but here consecration required seven days.

The text repeats it: “seven days” (vv. 33, 35)—day and night for seven days, carrying out all that the Lord commanded. Why seven? The number symbolizes completeness. Just as a wedding feast lasted seven days, and just as God created the world in seven days, so this week-long ordination marked a fundamental life change for the priests. From that moment forward, their calling was permanent.

So it is with our new life in Christ. As Ross rightly notes:

In the Gospels Jesus used the image of “taking up the cross” and following him. In the Roman world whoever took up a cross was led out to be crucified. The point is that they were not coming back. Jesus’ servants had to make that kind of commitment, totally new way of life.

This is why Paul compares marriage to Christ and the church. Marriage, rightly lived, is a lifelong covenant, a picture of our permanent union with Christ. Our installation into God’s service is not temporary—it is lifelong and eternal.

CHRIST OUR GREAT HIGH PRIEST

Now, one of the things that we should notice in this text is that as Aaron is being instituted as the high priest, and his sons as priests, but Moses is acting as the priest here. He’s never explicitly been called a priest, but in many ways, Moses is functioning as one. He is also acting in a way that foreshadows Jesus, acting as a prophet, priest, and king. Though in the Pentateuch he is only explicitly or indirectly called a prophet, notice that he is the one taking on this priestly service. That’s why we hear the repeated refrain after almost every paragraph of this chapter: as the LORD commanded Moses.

Moses is the archetypal priest who is ordaining the Levitical priesthood to minister in his place, which was necessary because Moses was going to die. Although he was incredibly faithful to God, Moses was still a sinner. So, more important than Aaron as the high priest, and more important even than Moses as the archetypal high priest who installs Aaron and his sons, is the greater fulfillment to which this all points. We should look to the greater Moses. We should look to the greater Aaron. And that is Christ, who is our true High Priest. Indeed, all seven of these elements of the consecration service find their fulfillment in Jesus Christ.

Jesus, too, was witnessed. His ministry was publicly witnessed by Israel, by many Gentiles, and supremely by the apostles, who then bore witness to the rest of the world. His ministry was also confirmed by God the Father. At His baptism, a voice from heaven declared, “This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased.” And in Acts 2, Peter tells the people on Pentecost, “Jesus of Nazareth was a man attested to you by God with mighty works.” So, Jesus was witnessed by the people and attested by the Father.

Jesus was also washed. Now, He wasn’t washed for the same reason Aaron and his sons were. Jesus underwent baptism even though He was sinless. He said it was “to fulfill all righteousness.” I believe this was Jesus identifying Himself with our sin. He wasn’t baptized for His own sin, but to identify with ours and to inaugurate His ministry—just as the washing of the priests inaugurated theirs.

Just as the priests were clothed, Christ too was clothed for His ministry. Isaiah 61:10 speaks of the servant of Yahweh clothed in righteousness and salvation. Christ was clothed with salvation so that He might rescue us. But unlike the priests, Jesus did not need outward priestly garments. He didn’t need to wear the colors of the tabernacle for His ministry. Instead, He took on our humanity. In His incarnation, Christ became the true and better tabernacle. John 1:14 says, “The Word became flesh and dwelt among us.” That word “dwelt” is literally “tabernacled.” Jesus is the true and better dwelling place of God with His people. By taking on flesh, retaining His full divinity and assuming full humanity, He became the perfect High Priest—the only one who can truly stand between God and man, because He is both God and man.

And Christ was also anointed. Indeed, Christ is the Anointed One—that’s what the word “Christ” means. David was a kind of anointed one, Aaron was an anointed one, but Jesus is the Christ, the Messiah. He wasn’t just anointed with oil as a symbol of the Spirit. He was filled with the Spirit Himself. At His baptism, when He came up from the water, He heard the Father’s voice affirming Him as His Son, and the Holy Spirit descended upon Him like a dove, anointing Him for His ministry. This is exactly what Isaiah 61 describes (“The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because He has anointed me”), which is a passage that Jesus Himself quotes in Luke 4.

Now, here is a hiccup in our formula: Christ was not atoned for; He has atoned us. Unlike the Old Testament priests, Jesus did not need atonement for Himself. Instead, He made perfect atonement for His people. Hebrews 7:27 says, “He has no need, like those high priests, to offer sacrifices daily, first for His own sins and then for those of the people, since He did this once for all when He offered up Himself.” Earlier the book of Hebrews also says He was like us in every respect, except without sin. And that is beautifully where Jesus is unlike the high priests. They needed to make atonement for their own sins before they could make atonement for the people. Jesus doesn’t need that. He is sinless, and He Himself is our atonement.

Jesus was ordained. Unlike the Old Testament priests, Christ perfectly fulfilled His ministry as a priest. As we noted above, the Hebrew word for consecration or ordination literally means “to fill the hands.” Andrew Bonar points out that the Septuagint uses the word τελειώσεως, which means fulfillment, perfection, or completion.

That same word appears in one of the most puzzling passages in Hebrews. In Hebrews 2:10 it says that Christ had to be “made perfect through suffering.” At first that sounds confusing. Why would Christ need to be made perfect? Isn’t He already perfect? Isn’t He God Himself in the flesh?

But Bonar explains that the word here is not speaking about Christ’s character—it is speaking about His office. Through His suffering, Christ was perfectly consecrated, perfectly ordained as our High Priest. His ordination was complete, unlike the ordination of the priests in Leviticus.

Lastly, Christ was also installed as priest. Just as the office of the priest in the Old Testament pointed forward to Him, Christ’s priesthood is permanent and unending. Hebrews 7:23–24 says, “The former priests were many in number, because they were prevented by death from continuing in office, but He holds His priesthood permanently, because He continues forever.”

Is that not good news? The priests of the Old Testament all died. Aaron dies in the book of Numbers and is replaced by Eleazar, his son. Eleazar dies and is replaced by his son, and on and on. But Jesus lives forever. Though He died on the cross, He did not stay dead. He rose from the grave and lives forevermore. That means right now, 2,000 years after His earthly ministry, Jesus is still our Great High Priest. He accomplished the work He came to do—He made perfect atonement for our sins once for all. And now He sits at the right hand of God the Father, ever living to intercede for us. He prays for us, pleads for us, and speaks before the Father on our behalf as His people.

Indeed, once they were consecrated and installed into their office, the priests were then ready for their ministry of bringing God’s people near to Him. Brothers and sisters, that is what Jesus has done and is doing still. On the cross, our Lord became the perfect offering, atoning for our sins once for all and reestablishing our communion with God. And here, through this bread and cup that set our eyes upon His finished work, He is continually drawing us near God as our Father, continually summoning us to repent of sin and to walk in peace and fellowship with Him. Therefore, as we eat this bread and drink of this cup, let us draw near to our great God through our mediator and high priest, Jesus Christ.