The LORD spoke to Moses… This text is the Word of God, of which Psalm 19:9 says: “the rules of the LORD are true, and righteous altogether.” God’s rules (and Leviticus is filled with rules) are true or, we could even say, are truth. They give us the testimony of the Creator of heaven and earth upon whose words we stand and breathe. None of God’s rules are trite or meaningless; instead, each expresses the reality which He Himself formed. And they are righteous altogether. None of God’s rules are for our harm or destruction but for our good and for His glory. As children complain about rules that they cannot yet understand, so do we often kick against the rules of God. But as we open the Scriptures this morning, let us cling to them as truth that is altogether righteous.

Without question, the Day of Atonement was at the heart of Israel’s calendar and life. It is also, as we considered in the opening chapter, the structural and thematic centre of the Pentateuch, the literary summit to which and from which the narrative drama ascends and descends. Indeed, the high priest’s narrated entry within the veil of God’s house is, for the reader, an entrance within the inner sanctum of the Pentateuch’s theology, the keystone of the cultic system of forgiveness of sins.

We come today to Leviticus 16. As Morales said and we have noted, Leviticus stands at the center of the Pentateuch. Genesis gives us the great problem of humanity’s sinfulness and exile from the presence of God. Chapters 1-11 show us the deepening exile, further down and further out, but chapters 12-50 give us the hope of God calling His people to Himself. In Exodus, God redeems His people from slavery and brings them to Himself in the wilderness. At the end of that book, the tabernacle is built, and God comes to dwell in their midst.

Leviticus answers this question: How can God’s sinful people have communion with Him? That is the heartbeat of the book. Numbers then shows us God’s discipline of Israel, and Deuteronomy commissions them to go in and inherit the land. So, Leviticus lays in the middle of the chiasm of the Torah.

But Leviticus itself is also a chiasm. Broadly, the whole book can be divided into two halves: drawing near to God and living in holiness to God. But those two halves are related to one another chiastically. The bridge between these two halves and the center of the chiasm is chapter 16: the Day of Atonement. This the mountain top of Leviticus, just as Leviticus is the mountain top of the Pentateuch.

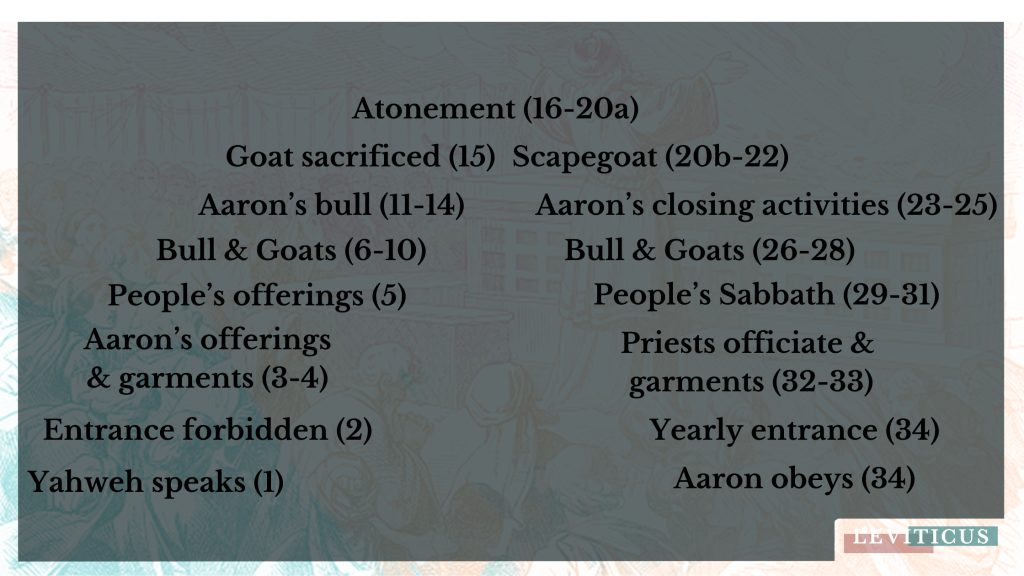

And even within this chapter, there is yet another chiasm, structures within structures. It begins with Yahweh speaking and ends with Aaron’s obedience. The command forbidding entrance parallels with the command for the high priest to enter once each year. But everything leads to the center of the chapter: atonement made for the people of God.

We have seen the word atonement already in the offerings. It literally means at-one-ment. It is reconciliation, the restoration of a broken relationship. As this chapter shows, it involves forgiveness of sins but also cleansing from impurity.

We saw this last week in chapter 12. After childbirth, a woman would bring a purification offering and burnt offering to make atonement. But childbirth was not sinful, only unclean. There atonement was about cleansing and restoring back into the normal rhythms of life among God’s people.

So too, here, the Day of Atonement captures both realities. The offerings in chapters 1-7 dealt with sin, while the purity laws in 11-15 dealt with ritual uncleanness, which were given to keep people from sinning against God’s holiness by entering His presence unclean. Here, those two themes unite together. Here, atonement is made for the sins of Israel, and atonement is also made for their uncleanness. Here, the tabernacle itself is cleansed from the accumulated sins and impurities of the people, and the people themselves are cleansed and forgiven. That is the purpose of this day: forgiveness of sins and cleansing from impurity, so that God can continue to dwell with His people.

APPROACHING THE HOLINESS OF GOD // VERSES 1-5

The LORD spoke to Moses after the death of the two sons of Aaron, when they drew near before the LORD and died, and the LORD said to Moses, “Tell Aaron your brother not to come at any time into the Holy Place inside the veil, before the mercy seat that is on the ark, so that he may not die. For I will appear in the cloud over the mercy seat.

This immediately ties us back to Leviticus 10, where Nadab and Abihu died for approaching God in a way He had not commanded. Between chapters 10 and 16, we have studied the purity laws, which all stressed the importance of Israel’s need to be clean int he presence of God. Now, chapter 16 intentionally connects back to chapter 10, bringing this immediately back to mind: God’s holiness is dangerous for sinners.

Now, the tabernacle itself was divided into two sections. The first, called the Holy Place, made up two-thirds of the tent. There stood the golden lampstand, the table for the bread of the Presence, and the altar of incense, which was placed before the veil. That veil separated the Holy Place from the Most Holy Place, the innermost chamber where the ark of the covenant was kept.

The ark was essentially a box overlaid with gold, and on top of it was the mercy seat, the golden cover. And here God says, I will appear in the cloud over the mercy seat. The very glory-cloud that led Israel out of Egypt and descended upon the tabernacle would manifest there. This was where heaven met earth.

And God says to Aaron, “You cannot come whenever you want.” The veil was not a decoration; it was both prohibition and protection. it guarded priests from rushing into the fire of God’s holiness.

And yet, verse 3 goes on to say: But in this way Aaron shall come into the Holy Place: with a bull from the herd for a sin offering and a ram for a burnt offering.

Aaron was permitted to enter only one day each year, and he must be prepared to do so. Chapters 10-15 have emphasized that no one can approach God’s presence flippantly and casually. How much less the high priest! Again, Ecclesiastes 5:1-2 is a fitting reminder:

Guard your steps when you go to the house of God. To draw near to listen is better than to offer the sacrifice of fools, for they do not know that they are doing evil. Be not rash with your mouth, nor let your heart be hasty to utter a word before God, for God is in heaven and you are on earth. Therefore let your words be few.

Of course, we have seen the importance of sacrificial offerings, but revenant listening to God is better than a hasty and careless sacrifice. Reverence, preparation, and humility are more important than ritual. Indeed, the point of ritual is to foster reverence, preparation, and humility.

Do we take that seriously? The same God who struck down Nadab and Abihu is the God who also struck down Ananias and Sapphira in Acts 5. He is also the same God that we still worship. Do we treat Him with reverence? Or do we imagine Him as just as our buddy, someone to laugh and joke with. Especially whenever we gather for worship, are we mindful of the gravity of what we are doing?

Notice, too, the garments of Aaron. Normally, the high priest was clothed in garments of glory and beauty: richly colored, adorned with gold, and bearing the breastpiece with the names of the tribes of Israel. But not on this day. On the Day of Atonement, he laid aside the splendor of those vestments and wore only four simple pieces of white linen. On this, Gordon Wenham comments:

On the day of atonement he looked more like a slave. His outfit consisted of four simple garments in white linen, even plainer than the vestments of the ordinary priest (Exod. 39:27-29). The symbolic significance of these special vestments is nowhere clearly explained. Undoubtedly they draw attention to the unique character of the occasion. On this one day the high priest enters the “other world,” into the very presence of God. He must therefore dress as befits the occasion. Among his fellow men his dignity as the great mediator between man and God is unsurpassed, and his splendid clothes draw attention to the glory of his office. But in the presence of God even the high priest is stripped of all honor: he becomes simply the servant of the King of kings, whose true status is portrayed in the simplicity of his dress. Ezekiel (9:2-3, 11; 10:2, 6-7) and Daniel (10:5; 12:6-7) describe the angels as dressed in linen, while Rev. 19:8 portrays the saints in heaven as wearing similar clothes.

Aaron did not come before God in splendor but in humility, clothed as a servant. And as Wenham noted, both angels and saints in heaven are dressed the same. The greatest of God’s servants–priests, angels, and saints–stand before Him not in their own glory but in the humble purity that only God can provide. Let us remember that truth well in this life. Whatever robes, splendors, and honors we have before men, in the presence of God we are all simply servants of the King. None of us can yet fully understand Jesus’ teaching. Who is greatest in the kingdom? The least, the slave of all.

ATONEMENT REQUIRES SACRIFICE // VERSES 6-28

These verses describe the actual rituals of the Day of Atonement. Verses 6-10 give us something of an overview, while verses 11-28 provide the four major parts.

Three animals are essential to the Day of Atonement. A bull must be given as a purification offering for Aaron and his household. Two goats were also given. One to be sacrificed, and the other to be sent to Azazel.

Verses 11-14 describe the first part of the ceremony: the bull and the incense.

Aaron shall present the bull as a sin offering for himself, and shall make atonement for himself and for his house. He shall kill the bull as a sin offering for himself. And he shall take a censer full of coals of fire from the altar before the LORD, and two handfuls of sweet incense beaten small, and he shall bring it inside the veil and put the incense on the fire before the LORD, that the cloud of the incense may cover the mercy seat that is over the testimony, so that he does not die. And he shall take some of the blood of the bull and sprinkle it with his finger on the front of the mercy seat on the east side, and in front of the mercy seat he shall sprinkle some of the blood with his finger seven times.

Aaron must kill the bull for his own sin. He then took a censer full of coals from the altar and two handfuls of sweet incense, beaten small, and brought them inside the veil. The cloud of incense would veil the mercy seat, lest he die. He also took the bull’s blood and sprinkles it on and before the mercy seat seven times.

Notice that Aaron could only enter the Most Holy Place with two items: the smoke of incense and the blood of sacrifice. The incense veils the mercy seat, reminding us that sinful man cannot look directly upon the presence of God. Even this wooden box, freshly built, once consecrated to God’s holiness, becomes too holy for human eyes. The veil of smoke is protection. And yet throughout Scripture incense also represents the prayers of God’s people.

So Aaron enters with blood and prayer. That is profoundly significant, for that is still how we draw near to God. We come before Him only by the blood of the Lamb, and we draw near through prayer. That is true whether we come privately in our personal time in God’s Word corporately in gathered worship. We still pray and rest in the blood of Jesus.

Second, in verses 15-19, the first goat is sacrificed for the people.

Then he shall kill the goat of the sin offering that is for the people and bring its blood inside the veil and do with its blood as he did with the blood of the bull, sprinkling it over the mercy seat and in front of the mercy seat. Thus he shall make atonement for the Holy Place, because of the uncleannesses of the people of Israel and because of their transgressions, all their sins. And so he shall do for the tent of meeting, which dwells with them in the midst of their uncleannesses. No one may be in the tent of meeting from the time he enters to make atonement in the Holy Place until he comes out and has made atonement for himself and for his house and for all the assembly of Israel. Then he shall go out to the altar that is before the LORD and make atonement for it, and shall take some of the blood of the bull and some of the blood of the goat, and put it on the horns of the altar all around. And he shall sprinkle some of the blood on it with his finger seven times, and cleanse it and consecrate it from the uncleannesses of the people of Israel.

After making atonement for his own sin, Aaron killed the goat of the purification offering for the people and brought its blood inside the veil, sprinkling it as he did with the bull’s blood. Kenneth Mathews notes that “The ritual atonement had two effects: The people’s ritual impurities were removed from the holy place, and the sins of the people were forgiven” (141). It cleansed the holy place from the collective ritual impurities the inevitably brought into the tabernacle, and it’s atoned for their actual sins against God’s law. Both categories were dealt with here, defilement and transgression.

Then Aaron was to go out to the altar and apply the blood of both the bull and goat, sprinkling it on the altar’s horns and consecrating it from the uncleanness of Israel. Even the altar itself must be cleansed every year. Just as it was purified before being used, it needed to be purified again each year.

That is the first goat, the sacrificial goat. It makes atonement, cleansing the uncleanness and securing forgiveness, so that God can continue to dwell among them.

Third, in verses 20-22, we read of the second goat, the scapegoat.

And when he has made an end of atoning for the Holy Place and the tent of meeting and the altar, he shall present the live goat. And Aaron shall lay both his hands on the head of the live goat, and confess over it all the iniquities of the people of Israel, and all their transgressions, all their sins. And he shall put them on the head of the goat and send it away into the wilderness by the hand of a man who is in readiness. The goat shall bear all their iniquities on itself to a remote area, and he shall let the goat go free in the wilderness.

If the first goat was about purification, this one was about removal. It is not cleansing but carrying away. The scapegoat bears the guilt of the people. Indeed, notice the presence of all three key words for sin in verse 21: iniquities, transgressions, and sins. Nothing is left out. Aaron confesses it, places it on the goat, and it is sent away.

But what does it mean that the goat is sent to Azazel? The word only occurs here, so we do not know for certain what it means. Here are the three primary views.

First, some think that Azazel refers to a demon, a goat-spirit of the wilderness rather like the Greek satyrs. Most who hold to this view do not believe that an offering is being made to the demon but that sending the goat away shows that sin belongs to the realm of death and judgment. But there is little evidence for that theory.

Second, it could also have referred to a particular location out in the wilderness, like a specific place that the goat was being sent toward.

But the most common interpretation seems to also be the most likely. Azazel means “the goat that is sent away”. In Hebrew, az means goat and azel means send off. That is how the Septuagint translated as well as the Vulgate, and from those, Tyndale created the term scapegoat. Indeed, scapegoat still means something similar to this, a person to takes the blame or takes the fall for something.

And that is clearly what is happening here. Aaron lays his hands on the head of the goat. Remember that laying hands on the offering could have meant a number of things, but here it is explicitly connected to confession of sin, placing them on the animal. And then the goat is sent into the wilderness, out of the camp, away from the presence of the LORD.

Can you see the portrait of Christ here? Hebrews 13 tells us that Jesus suffered outside the camp for us. Like the scapegoat, He was led outside the city, carrying the sins of His people on His shoulders. Meditate over Isaiah 53 as you think of the scapegoat. See Him being led away, outside Jerusalem, to Golgotha, bearing our sins in His body upon the tree.

The fourth and final part of the ritual is recorded in 23-28.

Then Aaron shall come into the tent of meeting and shall take off the linen garments that he put on when he went into the Holy Place and shall leave them there. And he shall bathe his body in water in a holy place and put on his garments and come out and offer his burnt offering and the burnt offering of the people and make atonement for himself and for the people. And the fat of the sin offering he shall burn on the altar. And he who lets the goat go to Azazel shall wash his clothes and bathe his body in water, and afterward he may come into the camp. And the bull for the sin offering and the goat for the sin offering, whose blood was brought in to make atonement in the Holy Place, shall be carried outside the camp. Their skin and their flesh and their dung shall be burned up with fire. And he who burns them shall wash his clothes and bathe his body in water, and afterward he may come into the camp.

Notice the flow of these verse. Aaron removes the special linen, washes himself, and then puts on his regular vestments again. After that he offers two burnt offerings, one for himself and another for the people. Once again, the text emphasizes atonement. It has already been stated several times, but repetition means pay attention. God’s people need to hear again and again: atonement has been made; your sins are forgiven.

The text then adds that one the one who releases the scapegoat must also wash before returning to the camp and that the carcasses needed to be burnt outside the camp. Anyone involved in these final acts must wash themselves before returning to the people because they had been handling what represented the sins of Israel. And the final step was a visible cleansing, emphasizing that the work was done.

Can you see the picture? Atonement had been accomplished. The tabernacle had been cleansed, their sins were forgiven, God would remain with them for another year.

ATONEMENT REQUIRES HUMILITY // VERSES 29-34

These verses conclude our text:

And it shall be a statute to you forever that in the seventh month, on the tenth day of the month, you shall afflict yourselves and shall do no work, either the native or the stranger who sojourns among you. For on this day shall atonement be made for you to cleanse you. You shall be clean before the LORD from all your sins. It is a Sabbath of solemn rest to you, and you shall afflict yourselves; it is a statute forever. And the priest who is anointed and consecrated as priest in his father’s place shall make atonement, wearing the holy linen garments. He shall make atonement for the holy sanctuary, and he shall make atonement for the tent of meeting and for the altar, and he shall make atonement for the priests and for all the people of the assembly. And this shall be a statute forever for you, that atonement may be made for the people of Israel once in the year because of all their sins.” And Aaron did as the LORD commanded Moses.

That phrase, you shall afflict yourselves, can also be translated as denying self. It is not common in Scripture, but Psalm 35 associates it with fasting. So, the sense is likely that God’s people were fasting, denying themselves in a visible way, to show their contrition over their sin. Indeed, that is how Jews still observe Yom Kippur today.

Noice also what God commands: not just Aaron, not just the priests, but the entire congregation. Everyone, native and sojourner alike, was to rest, to fast, and to humble themselves before the LORD. While Aaron alone could perform the rites, the people were not just spectators. Their role was to humble themselves, to take their sin seriously, and enter the day with solemnity.

And the reason is clear: For on this day atonement shall be made for you to cleanse you. You shall be clean before the LORD from all your sins. That’s the good news of the Day of Atonement. By the blood of the sacrifice, God cleansed His people from sin.

Now, how does this apply to us? Do we need to fast in order to prepare ourselves to receive Christ? No. The New Covenant does not call us to prepare ourselves like that. We do not need to make ourselves ready to come to Christ. The invitation is simply: Come.

But here is what does remain the same: only the humble can receive atonement. Israel showed their humility through fasting while Aaron made atonement for them. Under the New Covenant, humility is still required. You don’t necessarily need to fast, but you must set aside your pride.

“God opposes the proud but gives grace to the humble.” That is how God operates. The gospel requires no work from us; Christ has done it all. But that is what makes the gospel so difficult to receive. It requires admitting that we cannot save ourselves, that we cannot earn God’s favor, that we must trust completely in another. The difficulty of the gospel is its surrender, saying honestly, “I cannot save myself. I need Christ. He must save me, or I am lost.”

Atonement requires sacrifice, which is ultimately the work of Christ on the cross. But atonement also requires humility, which is our posture before Him. We must receive Christ in faith.

THE INSUFFICIENCY OF AARON

And Aaron did as the LORD commanded Moses.

Aaron was obedient. And because of that obedience, the sins of Israel were cleansed. They were forgiven. They had communion with God… for another year. But then, they would have to do it again and again and again.

Again, the problem with the old covenant was not its lack of grace or faith. This chapter is saturated with grace to be received through faith. The problem was its insufficiency. It could not truly and permanently deal with sin. All of this points ahead, by faith, to the true Day of Atonement, which is described for us in Hebrews 9. Just the Day of Atonement is as the center of Leviticus, Hebrews 9 sits at the literary center of that book as well, showing us the better priest, the better sacrifice, and the better covenant.

But when Christ appeared as a high priest of the good things that have come, then through the greater and more perfect tent (not made with hands, that is, not of this creation) he entered once for all into the holy places, not by means of the blood of goats and calves but by means of his own blood, thus securing an eternal redemption. For if the blood of goats and bulls, and the sprinkling of defiled persons with the ashes of a heifer, sanctify for the purification of the flesh, how much more will the blood of Christ, who through the eternal Spirit offered himself without blemish to God, purify our conscience from dead works to serve the living God…

Thus it was necessary for the copies of the heavenly things to be purified with these rites, but the heavenly things themselves with better sacrifices than these. For Christ has entered, not into holy places made with hands, which are copies of the true things, but into heaven itself, now to appear in the presence of God on our behalf. Nor was it to offer himself repeatedly, as the high priest enters the holy places every year with blood not his own, for then he would have had to suffer repeatedly since the foundation of the world. But as it is, he has appeared once for all at the end of the ages to put away sin by the sacrifice of himself.

The phrase once for all is the heart of Hebrews. Christ does not need to be sacrificed every year. He does not need to offer Himself again and again. His one sacrifice was enough. That means He is the true scapegoat, carrying away the sins of His people, not for only a year but forever. He is the true purification offering and the true burnt offering, reconciling us to God for all time.

And to prove it, when Christ died on the cross, the veil of the temple was torn in two. The barrier that kept Israel outside of the Most Holy Place was gone. The privilege that only the high priest had once a year, we now have every moment of every day. By Christ’s blood, we have continual access to God. We can come to Him in prayer. We can come to Him in His Word. We can gather with His people and know His presence.

Brothers and sisters, do you see the glory of Good Friday? That day, nearly 2,000 years ago, was the true Day of Atonement. Every sacrifice, every ritual, every year of Israel’s history– all of it pointed to Christ and His cross.

And notice this: just as the Day of Atonement cleanse the people but also purified the tabernacle for God’s dwelling, so also Christ’s death both cleanses us from our sin and purifies heaven for us. He makes it possible for us to enter into God’s presence forever. Therefore, as we come the Table of our King, let the words of Hebrews invite us further up and further in:

Therefore, brothers, since we have confidence to enter the holy places by the blood of Jesus, by the new and living way that he opened for us through the curtain, that is, through his flesh, and since we have a great priest over the house of God, let us draw near with a true heart in full assurance of faith, with our hearts sprinkled clean from an evil conscience and our bodies washed with pure water. Let us hold fast the confession of our hope without wavering, for he who promised is faithful. And let us consider how to stir up one another to love and good works, not neglecting to meet together, as is the habit of some, but encouraging one another, and all the more as you see the Day drawing near.